The high price of prescription drugs drives health care costs in the United States, where per-capita health care spending outstrips spending for the same products and services in other developed countries. The top five medications prescribed for diabetes and obesity represent a total annual expenditure of $157 billion to treat these two conditions in the United States.

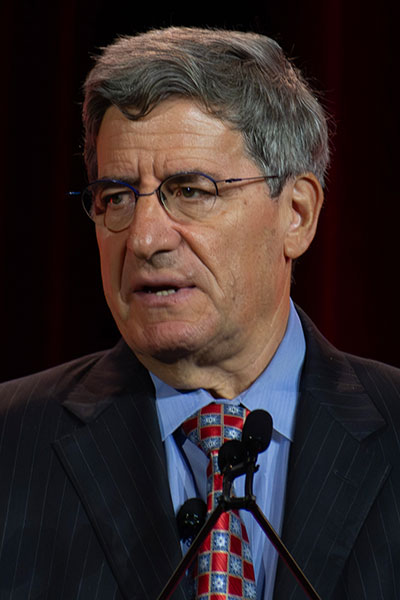

“When you then take these data in terms of cost per person, and look at the quality of health care we get, you can see that the United States is ranked 15th in the world. Taiwan is ranked at the top. There are only 111 countries ranked, so we’re really far down for the cost of what it is to look after people. One of the things that drives some of this cost is medications,” said session co-chair Steven E. Kahn, MB, ChB, Professor of Metabolism, Endocrinology and Nutrition, University of Washington (UW) and the VA Puget Sound Health Care System, and Director of the UW Diabetes Research Center and VA Puget Sound Health Care System Diabetes Research Group.

Dr. Kahn shared these statistics during ADA Diabetes Care Symposium—How Do We Fix a Broken Health Care System? at the 85th Scientific Sessions in Chicago.

“Our health care system does not value or prioritize the long-term health and wellbeing of all persons and communities and does not realize the full social return on health care investments,” said Marshall Chin, MD, PhD, who highlighted value-based payment and alternative payment models. “The system still largely rewards and incentivizes the provision of a high volume of services to a more profitable payer mix of privately insured patients rather than implementation of effective diabetes population health care models.”

Dr. Chin is the Richard Parrillo Family Distinguished Service Professor of Medicine, Associate Chief and Director of General Internal Medicine Research, Director of the Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research, and Director of MacLean Center for Clinical Ethics, University of Chicago Medicine.

Seth A. Berkowitz, MD, MPH, Associate Professor of Medicine and Section Chief for Research in the Division of General Medicine and Clinical Epidemiology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, shared a comprehensive view on how to address the dual problem of poor population health and high per-capita spending on personal health care in the United States relative to other developed countries.

While the two issues are interrelated because poor population health can lead to greater health care spending to try to treat those in poor health, Dr. Berkowitz said this isn’t the largest contributing factor to the situation in the United States.

“Our public policy does not create the conditions needed to be healthy for many people in the U.S.,” he said. “A key reflection of this is indicators of material deprivation, such as poverty, where you can see the U.S. is a leader among similar countries, and food insecurity, where the U.S. is also a leader among similar countries.”

These social determinants of health (SDOH)—the non-medical factors that influence health and wellbeing, such as the conditions in which people live and work, and their access to healthy food and reliable transportation—are shaped by the distribution of money, power, and resources, explained Namratha R. Kandula, MD, MPH, Professor of Medicine and Preventative Medicine at Northwestern University.

“Medical care is insufficient for ensuring better population health in our country. Improving population health in the U.S. requires all of us—health systems, health professionals, patients, community, social service organizations, and policymakers—to recognize and act on the SDOH as fundamental to our mission and to the health of all Americans,” Dr. Kandula said.

Because of the cost of medications, one in seven Americans with diabetes underuses prescriptions to drugs—by not filling prescriptions, taking lower doses than prescribed, or skipping doses—to treat their disease, reported Mariana Socal, MD, PhD, MS, MPP, Associate Professor of Health Policy and Management, John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

“Drugs don’t work if people can’t afford them,” she said, adding that, in the U.S., the cost of branded medication is three to four times higher than the cost of the same medication in other developed countries. However, U.S. patients pay 15% less for generic medications than their peers elsewhere in developed countries.

She went on to outline three policy solutions that could increase diabetes drug affordability for Americans:

- Incentivizing competition in the U.S. pharmaceutical market

- Expanding the Medicare drug price negotiation program

- Reforming the pharmacy benefit managers (PBM) compensation from drug prices by making PBMs fiduciaries of health plans

“I can tell you that there is strong bipartisan support for most of them, and they do have a very strong potential to actually improve affordability for all of us,” Dr. Socal said.

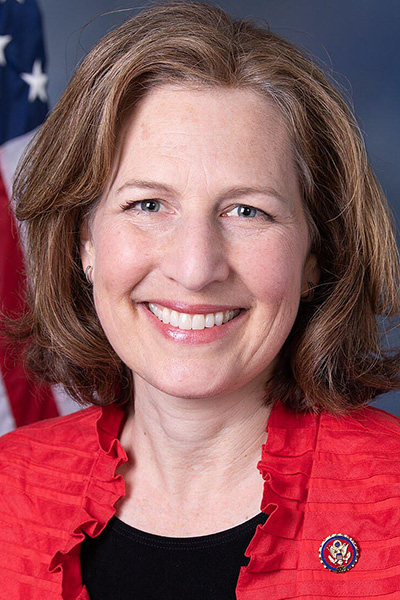

U.S. Rep. Kim Schrier, MD, of Washington, the first pediatrician to be elected to Congress, shared the perspective of a policymaker, a physician, and a person living with type 1 diabetes. She addressed funding for research and disease surveillance, such as the federally supported research that led to the development of COVID-19 vaccines in record time.

“The United States is the gold standard for research for a reason,” Dr. Schrier said in a video of her addressing Congress that was shared at the Scientific Sessions. “We have, in a bipartisan way, decided to fund the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in order to supply the resources to our most brilliant scientists at universities across the country to do the research that would allow the entire world to take leaps forward. And I think we are all so proud of this record of accomplishment in our country.”

However, earlier this year, the NIH instituted a cap on indirect research costs that it would fund. Dr. Schrier emphasized that indirect costs are just as necessary as direct costs like salaries for scientists.

“Indirect means that it may not be used for a single research project, but it could be used for the entire university,” she explained. “It could be the building, the equipment, the lab, the infusion center, the MRI machine. It could be the grant writers. It’s keeping the lights on. These are not insignificant needs.”

On-demand access to recorded presentations from this session will be available to registered participants of the 85th Scientific Sessions through August 25.

Watch the Scientific Sessions On-Demand after the Meeting

Extend your learning on the latest advances in diabetes research, prevention, and care after the 85th Scientific Sessions conclude. From June 25–August 25, registered participants will have on-demand access to presentations recorded in Chicago via the meeting website.